The Genesis of Electromagnetic Torque in Rotors: A Technical Analysis

This article dissects the fundamental physics governing how electrical energy acts upon the rotor to produce rotational motion, utilizing principles from Maxwell’s equations and Lorentz force laws.

1. The Fundamental Principle: Interaction of Fields

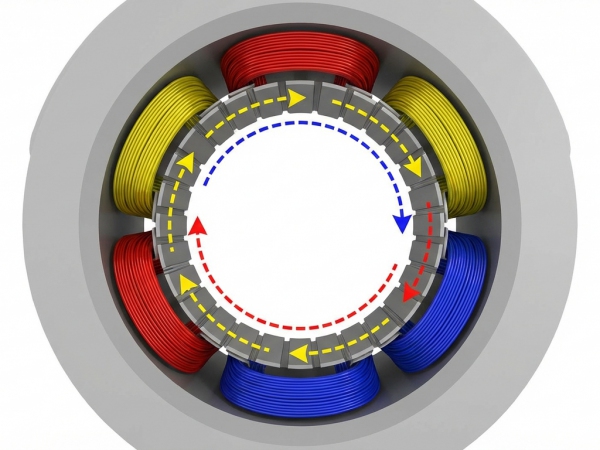

At its core, electromagnetic torque (T_e) is the result of the interaction between two magnetic fields. regardless of the motor topology (Induction, Synchronous, or BLDC), torque is produced due to the tendency of the rotor's magnetic field to align with the stator's magnetic field.

However, the mechanism of how the rotor acquires this magnetic field differs. For the purpose of this technical analysis, we will focus on the Induction Motor, as it represents the most complex instance of torque formation involving induced currents.

2. The Sequence of Torque Formation

The creation of torque in an induction rotor follows a specific causality chain. This process occurs instantaneously in real-time operation but can be broken down into four distinct physical stages:

Phase A: Generation of the Rotating Magnetic Field (RMF)

When a three-phase AC supply is applied to the stator windings, it generates a magnetic flux (\Phi_s) that rotates at synchronous speed (N_s). This flux crosses the air gap and cuts across the rotor conductors.

Phase B: Faraday’s Law of Induction

Since the rotor is initially stationary (or rotating at a speed N_r < N_s), there is a relative speed difference—known as slip—between the RMF and the rotor conductors.

According to Faraday’s Law of Electromagnetic Induction, this changing magnetic field induces an electromotive force (EMF) in the rotor bars.

E_{rotor} = -N \frac{d\Phi}{dt}

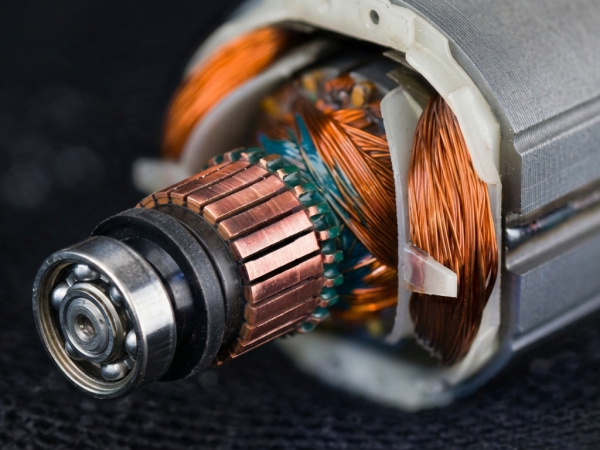

Phase C: Current Circulation

Because the rotor bars are short-circuited by end rings (in squirrel cage motors), the induced EMF causes a heavy current (I_r) to flow through the rotor conductors. Per Lenz’s Law, the direction of this current opposes the cause that produced it (the relative motion).

Phase D: The Lorentz Force Mechanism

This is the critical stage of torque production. We now have a current-carrying conductor (I_r) immersed in a magnetic field (B). According to the Lorentz Force Law, a mechanical force (F) is exerted on the conductor.

The vector formula is:

\vec{F} = I (\vec{l} \times \vec{B})

Where:

-

F is the Force vector.

-

I is the Rotor Current.

-

l is the length of the conductor.

-

B is the Magnetic Flux Density.

This force acts tangentially to the rotor surface. The summation of these tangential forces multiplied by the rotor radius (r) results in the Electromagnetic Torque (T_e).

3. Mathematical Representation of Torque

From a steady-state perspective, the electromagnetic torque can be expressed as a function of the air gap power (P_{ag}) and the synchronous speed (\omega_s).

T_e = \frac{P_{ag}}{\omega_s}

However, looking at the electromagnetic interaction variables, the torque is proportional to the product of the stator flux, rotor current, and the power factor of the rotor:

T_e \propto \Phi_s \cdot I_r \cdot \cos(\theta_r)

-

\Phi_s: Stator Flux.

-

I_r: Rotor Current.

-

\cos(\theta_r): Rotor Power Factor (representing the phase angle between induced voltage and current).

This equation highlights that torque is not just about having high current; it requires the current to be in phase with the magnetic flux for maximum efficiency.

4. The Influence of Slip on Rotor Torque

In induction motors, slip (s) is the variable that dictates the magnitude of torque.

-

At Start (s=1): The relative speed is maximum, inducing high EMF and current. However, the rotor frequency is high, causing high rotor reactance, which lowers the power factor. This results in standard Starting Torque.

-

At No-Load (s \approx 0): The rotor creates almost no torque because the rotor speed matches the magnetic field speed, meaning no flux lines are cut, and no current is induced.

-

Breakdown Torque: There exists a critical slip point where the balance between rotor resistance and reactance produces the maximum possible torque (Pull-out Torque).

Conclusion

The formation of electromagnetic torque in a rotor is a sophisticated interplay of magnetic induction and mechanical dynamics. It relies on the precise alignment of the stator's magnetic flux and the rotor's current vectors. For electrical engineers, mastering these principles is essential for optimizing motor control strategies, such as Field Oriented Control (FOC) and Direct Torque Control (DTC).

Related Articles

- Quality essentials of hydrostatic test for explosion proof motor (02/03/2026)

- What special requirements are there when the explosion-proof motor is overhauled (02/03/2026)

- Operating Principles of the Three-Phase Asynchronous Motor (12/08/2024)

- Special Requirements for Overhauling Explosion-Proof Electric Motors (12/08/2024)

- Quality Requirements for Hydrostatic Pressure Testing of Explosion-Proof Electric Motors (12/08/2024)